Cross referenced from http://gpue-group.github.io/.

One of the major components of GPUE is the ability to track and manipulate vortices in Bose-Einstein condensates. While we can work with creating vortices in 3D, the majority of the vortex creation and manipulation framework exists solely in 2D. This is due to the 2D vortex code being developed for the project on vortex dynamics, published in PRA here (arXiV version here).

To allow us to track and manipulate vortices in (2D) condensates, we require some numerical techniques and tools:

- Vortex detection.

- Vortex position refinement

- Vortex unique identification and tracking.

- Lattice model creation and arbitrary phase control.

1. Vortex detection

To find a vortex in the condensate, we can rely on several methods, such as tracking the condensate density minima. However, given the nature of the wavefunction (a complex valued scalar field), and a quantum vortex (topological defect of the wavefunction), we can examine the phase of the condensate, , such that . Every vortex in the condensate will have integer winding in the complex plane, wherein the phase has a singular point around which it winds through . By examining the condensate for these phase windings, we can identify the presence of a vortex to a location on our numerical grid.

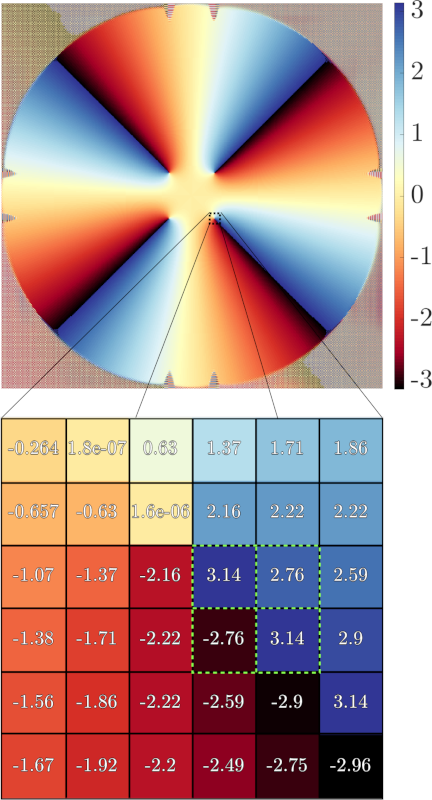

|

|---|

| Fig. 1: Plot of the wavefunction phase, , showing the values around a vortex core. |

The above image show the phase of a condensate containing four vortices. The zoomed region shows the numerical values of the sampled grid near this vortex core. By following a closed path around the dotted green line the the vortex core can be determined when the value is , positive for vortices, negative for anti-vortices (ie, vortices rotating in the opposite direction). In this instance, From the above plaquette, we can say that a vortex core has been identified, and as a result, we can keep note of the planar indices corresponding to this.

2. Vortex position refinement

With the above formalism, we can identify the vortex core to the region of a grid plaquette. However, we may also determine a better sub-grid resolution position of the core, by realising that a vortex core corresponds with a zero-crossing in the wavefunction for both the real and imaginary components. Following the formalism discussed in O’Riordan, 2017, and based on work carried out by Foster, 2013, we can calculate the 2D deviation from 0 in for the phase within this region, , and use this value to update the position as .

For this we use the least-squares formalism, and attempt to minimise the function with our observations as The integers are the indices in our plaquette (asuming clockwise or counter-clockwise is fine, provided we are consistent). Our matrix represents the data points, such that , on which we sample our wavefunction, and can be defined as

The minimisation problem can be solved by setting . For a given and , with an unknown position , and an approximate vortex plaquette position, , we can determine the unknown as

The resulting then becomes

From this, we can determine the correction to the vortex plaquette position using , and by solving the linear system

which allows us to examine the zero crossings in both the real and imaginary planes for both and dimensions. Using this approach our vortex positions are now siginificantly more accurate, and can be used to allow trajectory calculations, and statistical properties. When tracking vortices, the condensate outputs their discovered positions into a CSV file vort_arr_XYZ, one for every printed wavefunction time-point XYZ. A sample output of the CSV file format is

# X, X_refined, Y, Y_refined, Winding

485,4.858494e+02,485,4.858132e+02,1

485,4.858717e+02,538,5.381655e+02,1

538,5.381728e+02,485,4.858345e+02,1

538,5.381506e+02,538,5.381441e+02,1

for a given four vortex condensate. The values for positions are given in terms of the numerical grid coordinates. To determine actual positions, for a given simulation, it is necessary to examine Params.dat, and check the grid-size (), grid-increments (), and normalise the values from 0. As an example, . For the above simulation, , , given a position of for a condensate centered on at grid point (or if you are a 1-based indexing person).

3. Vortex unique identification and tracking.

If we are interested in statistical quantities such as vortex count, average separation, or distribution of windings (rotation directions), we can use the above methods. However, sometimes we wish to indentify and track unqiue vortices over the course of a simulation. As we are employing a field-based simulation in GPUE, namely solving the Gross-Pitaevskii equation for the wavefunction at points in time, we cannot maintain knowledge of our vortices between timesteps — each newly simulated wavefunction follows no particle objects. Instead, we must re-run the above tracking methods for each wavefunction at points in time to determine the vortex positions.

Given these newly determined vortex positions, it is important to identify which vortices at previous timepoints correspond to vortices in the current timepoints. For this, we rely on the unordered vortex positions file vort_arr_XYZ, and the Python script py/vort.py. This file reads all available vort_arr_XYZ files, creates a vortex with a unique index, maintains it in a linked-list (the ability to move and link vortices becomes important for larger condensates). For every vortex, at timepoint , the identified vortices at are compared, with a distance threshold set to determine if the vortex within a given radius could have moved through the set range between the timesteps. The vortex that is closest between timesteps is identified as the successor of the previous time-points unique index, and the list is updated to reflect this new information.

Upon processing this data, py/vort.py outputs a new file vort_ord_XYZ.csv, which can be used to examine vortex trajectories over time. The new CSV file changes the output format to # X_refined, Y_refined, Winding, UID, onFlag. The onFlag in this instance is used to indicate whether a vortex which was found at an earlier time point exists at later time points. Given certain perturbations can remove vortices from the condensate, this flag is a useful indicator of the physical behaviour. It is worth nothing, the the first 2 timepoints of analysis do not output files, as these are used to set-up the ordering of the later observed vortex data.

4. Lattice model creation and arbitrary phase control.

For condensates with multiple vortices, it is well known that the vortices arrange themselves into an ordered lattice. Therefore, it can be useful to have a lattice model for the vortices in rotating condensates. The C++ files "include/lattice.h", "include/node.h", "include/edge.h" define the function signatures that create lattices of vortices, and maintain this structure as a graph. Each vortex represents a node having a unique index and the previously determined positions, the nearest vortices are connected as edges determined by nearest-neighbour distances, and the overall structure is maintained as a lattice. This data structure allows us to address specific vortices in the condensate, read their properties, and even manipulate them before output to a vort_arr_XYZ file.

Given the ability to index a vortex, we can also implement functions that operate on the vortices at given positions. For a vortex at position , one such application of the lattice model is that we can modified the phase at this position. For the previously mentioned work, we chose to annihilate and add vortices to the condensate at pre-defined positions by applying the required phase profile to vortex core. As such, the lattice model allows one to read this position directly for a vortex of arbitrary UID, and use the resulting position for further manipulations. Such functions to apply arbitrary phase profiles are defined in include/manip.h.